Why I Modified My Great-Great-Grandfather's Watch

Few people are lucky enough to receive an heirloom watch in their lifetime. Of those people, even fewer are passionate about or even interested in watches. This past Christmas, I fell into that small Venn diagram. My grandfather gifted me his grandfather’s 1937 Hamilton Richmond: a solid 18k gold tonneau-shaped beauty oozing with early-20th-century charm.

As inscribed on the caseback, it was given to Anton Nielsen (my great-great-grandfather) by Hammermill Paper Company (his employer) in recognition of 20 years of faithful service. The watch is in great condition: my grandfather rarely wore it and, within the past 10 years, he had the movement overhauled and serviced. The vertically-brushed dial looks great, the crystal is without any deep scratches or cracks, and to the best of my knowledge, no parts (with the exception of a mainspring, I imagine) have been replaced. So, why in the world would I modify this watch in any way shape or form?

Some Background On Early-Mid Century Hamilton Watches

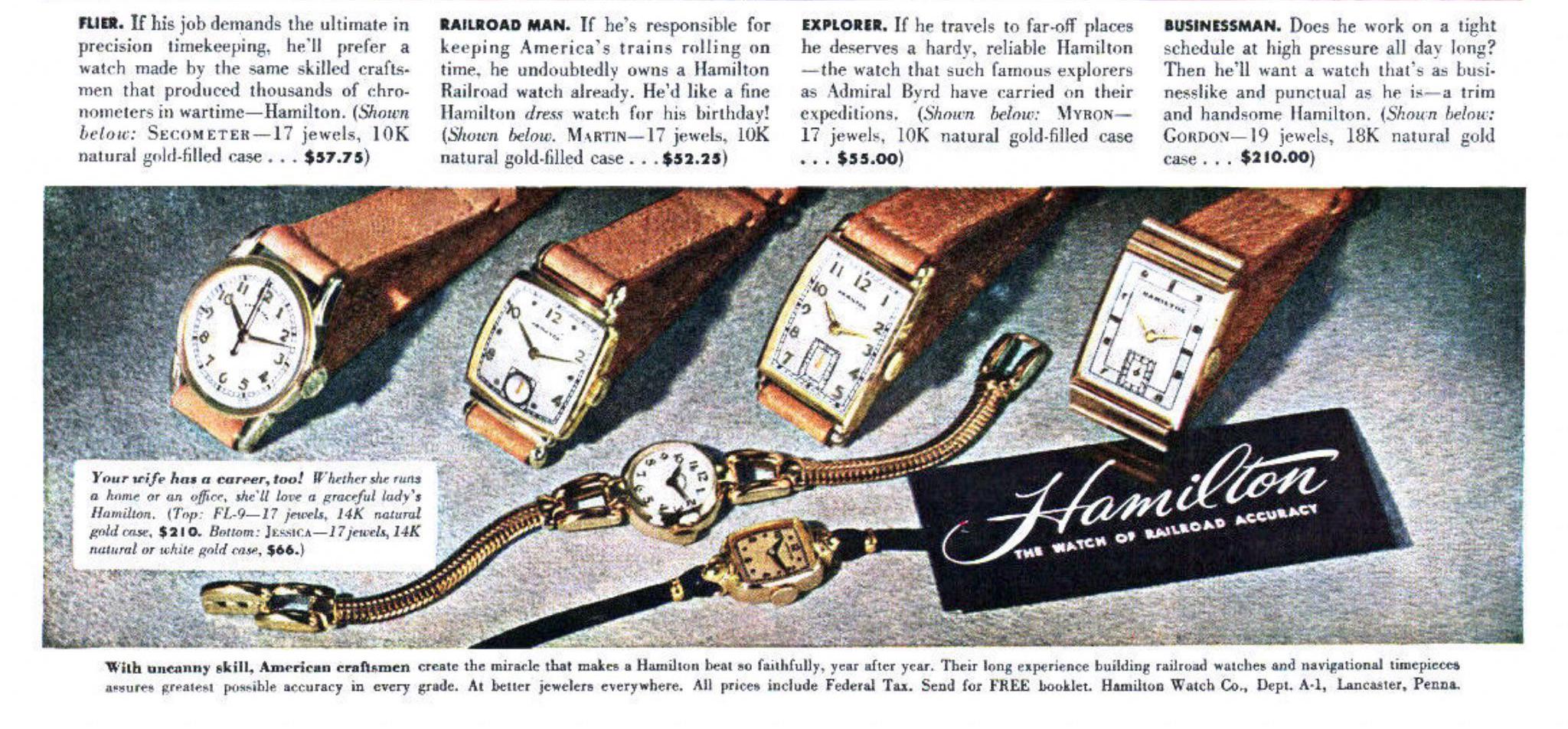

I won’t bore you with too long of a history lesson, but I can’t skip over what makes early-mid-century Hamilton watches so special. Hamilton Watch Company played a huge role in US railroad expansion. This was the basis of their success approaching the 20th century: creating robust, accurate pocket watches to time the departure and arrival of trains. Into the 20th century, Hamilton expanded by creating consumer-driven wristwatches. Because of their background manufacturing railroad chronometers, these little everyday watches were incredibly well-made and dead-reliable. Some refer to pre-Swatch Hamilton as “the American Patek.” (I won’t touch that one, just throwing it out there)

During World War II, Hamilton and other American watch brands halted production of consumer products, fulfilling government orders of military-issued watches. It’s often said that this contributed to the downfall of American watchmaking, as Swiss alternatives flooded the US market in lieu of domestic offerings.

The Hamilton Richmond

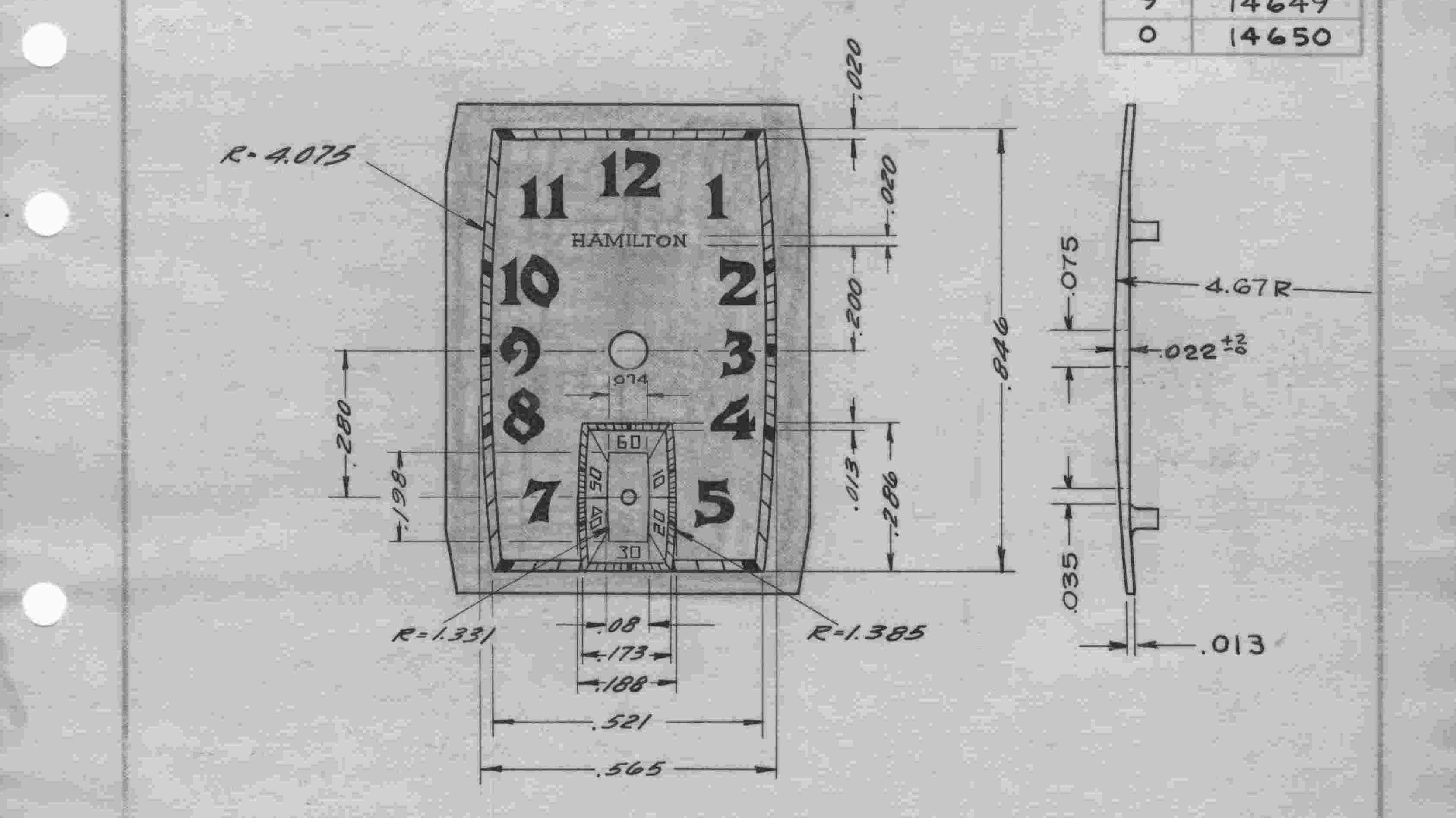

The Hamilton Richmond – among the last pre-war Hamilton wristwatches – is absolutely gorgeous. Thanks to Mark at vintagehamilton.com, I’m able to share a copy of Hamilton’s original design for the Richmond dial (pictured above). The stylized applied gold numerals, “moderne” handset, and railroad track around both the dial and small seconds subdial are, in a word, charming. For me, the tonneau-shaped case is what makes this watch so special. It wears more like a bracelet than a wristwatch.

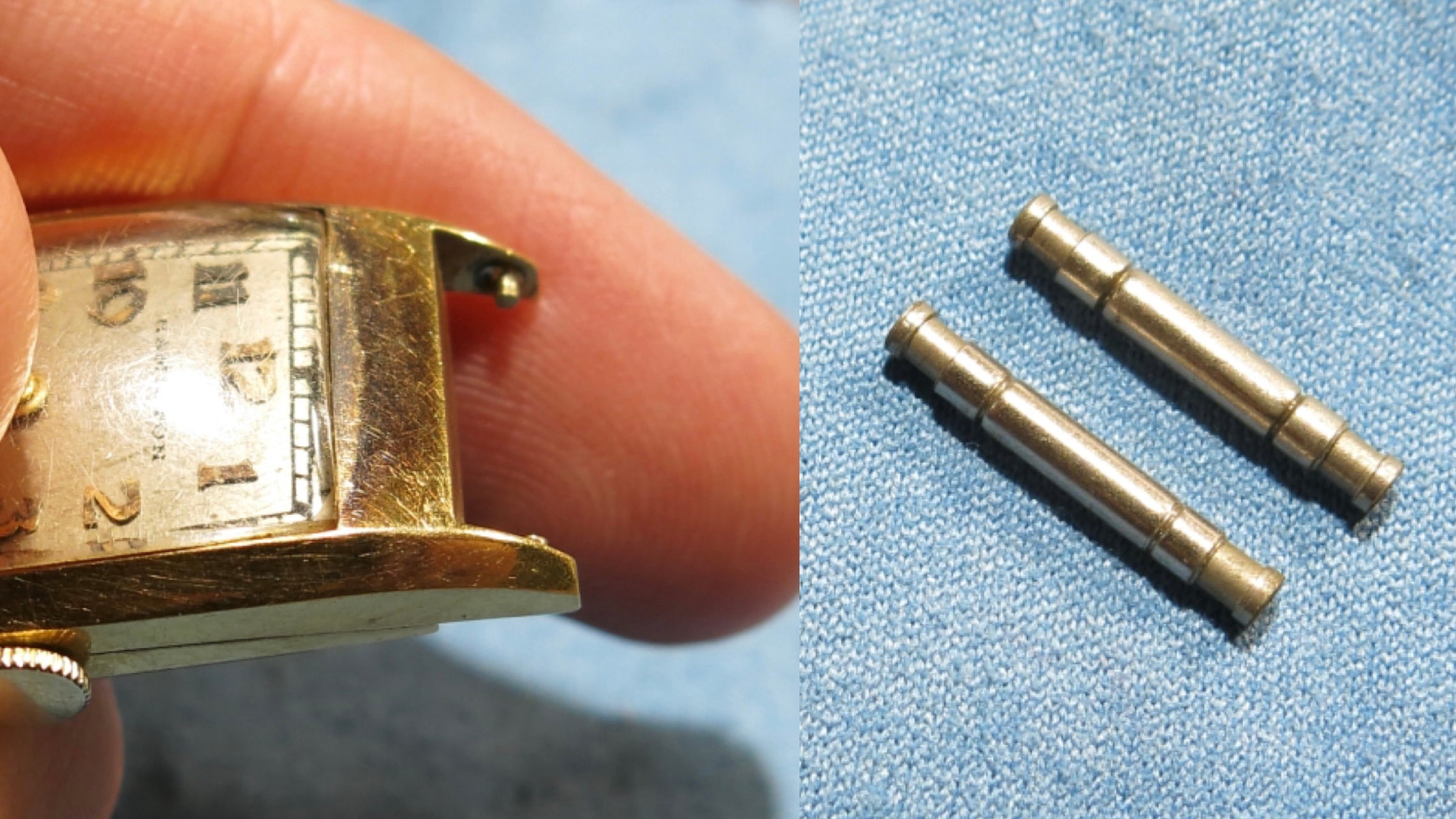

The Richmond features a design characteristic that was somewhat standard at the time: “female springbars." Instead of the springbar system you’re likely accustomed to – lugs with small bores that accept traditional springbars – the Hamilton Richmond features lugs with fixed protrusions (lug pins) that accept springbars with bores, or “female springbars.”

Hamilton Richmond lug pins (left) and female springbars (right). Images courtesy of hamiltonchronicles.com

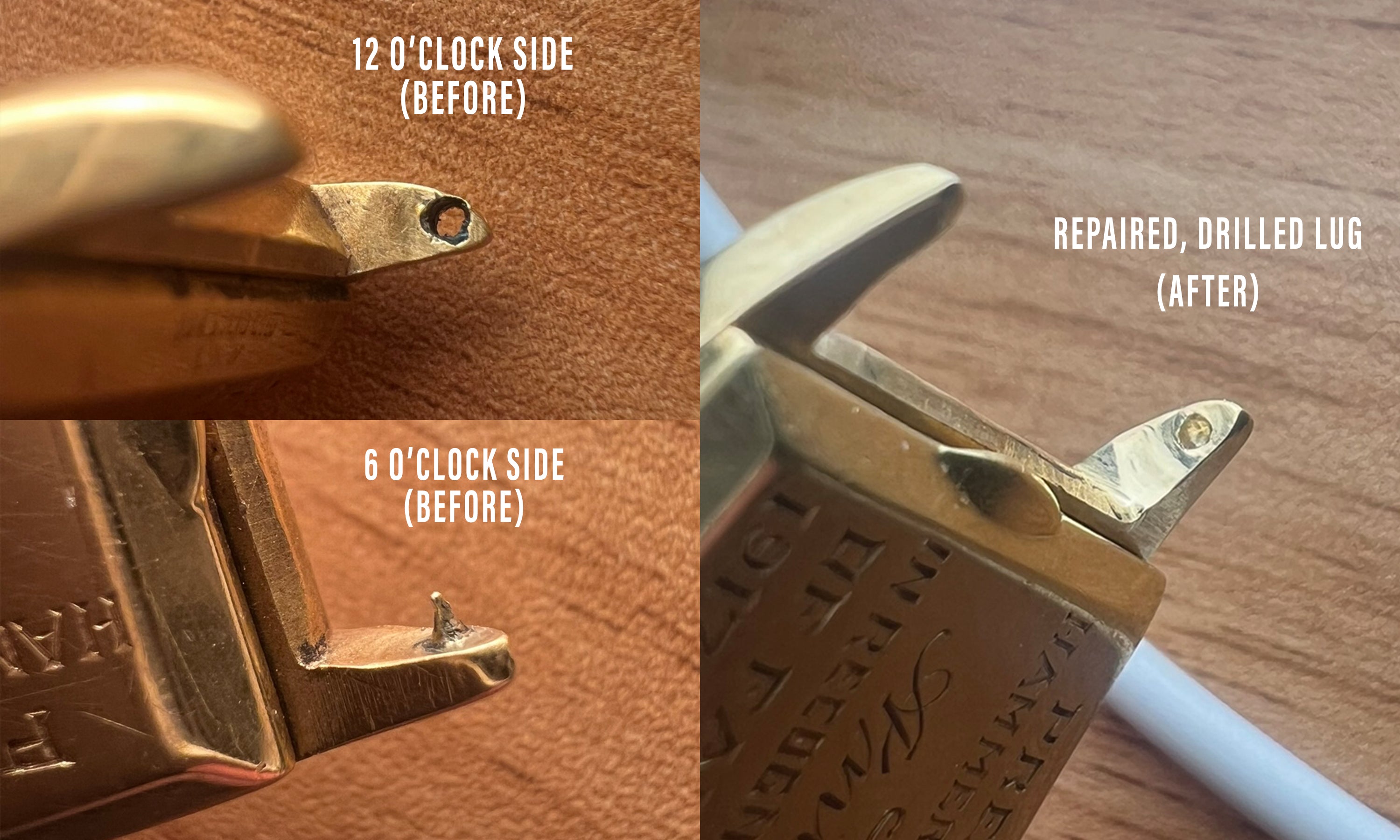

When I received the watch, my grandpa advised me to replace the strap, something I planned on doing sooner rather than later. Upon taking a springbar tool to the lugs, the 12 o’clock side of the strap came off as expected. It wasn’t until the 6 o’clock side that I ran into some difficulty. Come to find out, the 6 o’clock side retained the original lug pins (though very worn down) and a female springbar, while the 12 o’clock side was drilled to accept traditional springbars. Looking a bit closer, this drillwork was less than uniform, with one lug drilled all the way through and the other drilled about halfway. Further, the fully-drilled lug was warped and worn-down such that it was at risk of snapping. All of this is pictured below.

Why I Modified My Great-Great-Grandfather’s Wristwatch

At this point, you probably realize how and why I modified my great-great-grandfather’s Hamilton Richmond. Because the 12 o’clock side was already drilled to accept traditional springbars, and pretty shoddily at that, the decision was essentially made for me. I took the watch to a local watchmaker (who referred me to a trusted jeweler), and requested that the lug pins be drilled and the DIY lug holes be filled and re-drilled. Luckily, this jeweler did a great job at a reasonable price.

While I had my hesitations about taking in a newly-acquired heirloom for reconstructive surgery, I knew that if it were done well, it would result in a watch that’s both structurally sound and compatible with modern straps. As someone who likes to swap out straps and actually wear my watches, I knew that this modification had to be done. Needless to say, I’m elated with the results. As I mentioned earlier, very few people are lucky enough to receive an heirloom watch. By modifying the lugs to accept traditional springbars, I bought myself infinitely more optionality, ease of use, and subsequently, life out of this incredibly special piece. I’m beyond grateful to be able to wear my great-great-grandfather’s watch.

Leave a comment